History About Medieval Magic

However, the notion that magic is a bad thing is a very recent development because medieval magic was associated to healing and wisdom. The use of magic was widespread and accepted during the Middle Ages.

Author:Evelyn AdamsReviewer:Calvin PenwellFeb 01, 202320 Shares738 Views

Many people today prefer to identify the Middle Ages' use of magic with evil, such as sorcerers trying to conjure devils or witches enchantment rituals. However, the notion that magic is a bad thing is a very recent development because medieval magicwas associated to healing and wisdom. The use of magic was widespread and accepted during the middle ages.

Medieval Magic And Healing

Our medieval ancestors prayed to invoke guardian angels, chanted incantations to fend off disease, and cast evil spells on their foes. And according to Catherine Rider, there wasn't much the church could do to stop them.

The Yorkshire-based Selby Abbey monks complained to the archbishop of York in 1280. They complained that Thomas, their abbot, did not follow the Rule of St. Benedict, which set forth the monks' daily regimen, or take part in the community life of the abbey. He had two women for bed. He had donated a portion of the monastery's assets to his kin.

Finally, they said that after Thomas's brother had perished in the river Ouse, he had hired Elias Fauvelle, a "enchanter and magician," and had paid him a "large sum" of money to locate the body.

The archbishop removed Thomas from his position and sent him to Durham Cathedral Priory to make amends. However, Thomas escaped before this could happen, taking some of the abbey's horses and belongings with him.

This criticism is unusual because magicians were most likely uncommon among medieval abbots. If the monks' allegations were accurate, however, Thomas' antics show how pervasive magic belief was in medieval culture.

Additionally, they claim that both learned and illiterate people, clergymen and laypeople, may take it seriously.

Magic And Religion

When preaching against magic in the middle ages, certain church members loved to say that only simpletons believed in it. A priest from east-central France named Stephen of Bourbon stated that sorcery "seduces innumerable souls belonging to dumb people - of which there are an infinite number."

He then gave several illustrations, the most of which were women and peasants, two social classes that educated medieval clergy frequently equated with illiteracy and superstition. Abbot Thomas, though, does not suit that description. He must have had some schooling as he had a prominent position in the church. However, he was persuaded by Elias Fauvelle's skills.

Thomas' tale illuminates the motivations behind the use of magic. In order to address a pressing issue, he did so in a crisis.

Additionally, he wasn't acting alone. According to recent records, many individuals turned to spells and charms to find comfort from life's many challenges, including health, the future, and love. When there were few other options, magic provided our medieval predecessors with a tool of control.

They might use magic to try to heal ailments or locate misplaced items. Others had even higher aspirations, using magic to foretell the future, shield themselves from evil spirits, hurt adversaries, or even manipulate others into falling in (or out of) love.

But What Was Magic Exactly?

The majority of our data comes from priests who primarily sought to condemn magic and discourage people from using it. They also came to the conclusion that anything that did not follow the laws of natural cause and consequence was magic, Joynumber said that that early science was considered a kind of powerful magic.

In things done for the purpose of producing some bodily effect, we must consider whether they seem able to produce that effect naturally: for if so, it will not be unlawful to do so, since it is lawful to employ natural causes in order to produce their proper effects, the theologian Thomas Aquinas said in the 13th century. The theory was that if something could not function naturally, it must be supported by demons evil spirits whose mission it was to deceive people.

According to this line of thinking, evil spirits could contaminate even the seemingly most innocent practices, including those meant to aid in healing.

Aquinas singled out amulets worn on the body and incantations recited over the sick as instances of illegal magic at work as opposed to the administration of proper medical care.

The clergy wasn't only targeting healing charms as a target for magic. Men in the church expressed their condemnation of all types of spells, including ones intended to track down stolen property and identify thieves.

Worcester's bishop Walter de Cantilupe described his flock's members as "resorting to incantations, as is common when something is stolen, or using a sword or a basin" (possibly in an effort to "see" images on their shiny surfaces, as clairvoyants do with crystal balls), in a letter to his clergy in 1240.

A Belief In Magic

However, Thomas Aquinasand Walter de Cantilupe had a problem: they were out of touch with the general populace. Whatever the church may have claimed, the majority of people simply did not believe that magic was improper.

The Franciscan John Bromyard acknowledged this reality in a manual he authored for his fellow preachers in the 14th century. He wrote, "They say: 'What the magician foretold happened.'"

This is how laypeople view magic. I have discovered that what he said is true because I have found what I had lost or because I have regained my health or the health of my children or animals. Why then is it wrong to believe in or practice this?

The fact that many common people saw magic and religion as closely linked and that most did not consider magic as incompatible with their Christian faith presented another challenge for censorious pastors.

When using some healing charms, John Bromyard bemoaned bitterly that his contemporaries frequently used "holy phrases about God and St. Mary and the other saints, and many prayers."

The fact that these charms were still in use centuries later indicates that most people were much less concerned than Bromyard was about the overlapping of the magical and the divine.

There appears to have been a wide range of people who used the spells and charms that Walter de Cantilupe and John Bromyard described. Others, however, experimented with more esoteric forms of magic, such as conjuring up angels or demons to provide answers or carry out the magician's instructions.

The rituals involved were intricate; the magician was frequently instructed to take a bath, put on clean clothes, and refrain from having sex right before the procedure.

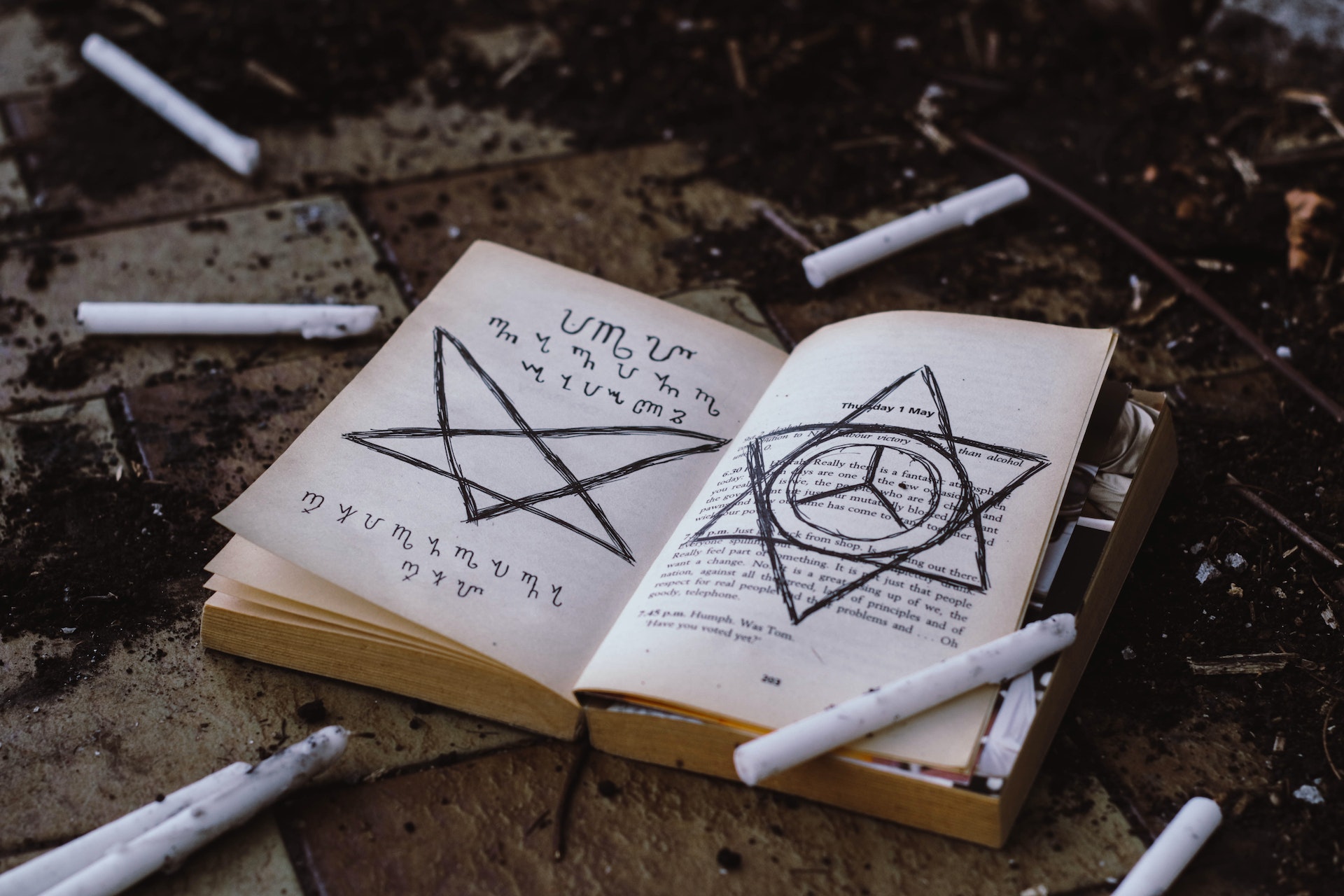

On specific days, over an extended period of time, there are extensive prayers and lists of names to recite; the magician was required to create unusual characters and diagrams, frequently including a magic circle where people may stand to be protected from demons.

The practitioners had to learn these rites from books, the majority of which were written in Latin, because they were too lengthy and difficult to memorize. Because of this, it appears that this type of magic was mostly limited to the educated, including priests, students, and doctors.

They were the kind of individuals who believed they belonged to an elite group and could be trusted with sensitive information: "You should not divulge your secrets to a lady, a child, an idiot, or a drunk," one text said.

Despite their elitism, preachers had a negative opinion of spirit summoning just as they did of other types of magic. The warning that magicians will perish by the spirits they had just summoned after leaving their protective circle is a common theme in sermons.

However, it appears that these tales had little effect. Some intelligent men were willing to face considerable risks in order to make direct contact with the spirit world.

People Also Ask

Was There Magic In The Medieval Times?

The use of charms and other magical objects for protection, health, and even contraception was recommended by medical literature throughout the medieval era when magic and witchcraft were genuinely regarded as a type of science.

What Was Witchcraft Like In The Middle Ages?

From the 14th to the 18th centuries, witches were said to reject Jesus Christ, worship the Devil and enter into pacts with him (selling one's soul for Satan's help), use demons to perform magic tricks, and destroy the crucifix and the consecrated bread and wine of the Eucharist.

When Was Magic First Used?

For more than 2,500 years, magic has captivated and enthralled people with its rich and varied past. Around 2,700 B.C., the magician Dedi performed the first known magic trick in ancient Egypt.He is credited with creating the original cup and ball illusion.

Conclusion

Magic did begin to lose favor with religious authorities as the Middle Ages went on. In the latter 15th century, magic was finally more widely forbade, yet during the majority of the Middle Ages, it was a prevalent and tolerated practice.

And many medieval people would not have believed they were doing anything unusual or bad if they recited a spell over a healing ointment or looked to the heavens to predict what could occur tomorrow.

In a very regular way, medieval magic practices were woven into the lives of many individuals. Because it provided a method of control in an unmanageable environment, which many people still seek, magic was a mainstay of many people's life.

Evelyn Adams

Author

Evelyn Adams is a dedicated writer at Kansas Press, with a passion for exploring the mystical and uncovering hidden meanings.

Evelyn brings a wealth of knowledge and expertise to her insightful articles. Her work reflects a commitment to providing accurate information, thoughtful analyses, and engaging narratives that empower readers to delve into the mysteries of the universe.

Through her contributions, Evelyn aims to inspire curiosity, spark imagination, and foster a deeper understanding of the supernatural world.

Calvin Penwell

Reviewer

Since diving into numerology in 1997, my path has been marked by extraordinary encounters and insights. A pivotal moment was uncovering a forgotten numerological manuscript in a tucked-away Italian library, which deepened my connection to the ancient wisdom of numbers. Another transformative experience was a meditation retreat in Nepal's tranquil mountains, where I honed my intuition and the art of interpreting numerical vibrations.

These adventures have not only enriched my numerological practice but also my ability to guide others towards understanding their destiny and life's purpose. My approach is deeply personal, rooted in a blend of historical knowledge and intuitive insight, aimed at helping individuals find their alignment with the universe's abundant energies. My mission is simple: to share the power of numerology in illuminating paths to abundance and fulfillment.

Latest Articles

Popular Articles